Food insecurity in Central Florida: Economic and Health Implications

by Alexis Tsoukalas, MSSA; 2020-2021 Thrive Economic Stability Fellow

With the onset of COVID-19, more Central Floridians are experiencing hardships than possibly ever before. Hunger or the fear that you don’t know where your next meal is coming from are chief among these hardships for far too many. As of the latest projections, every county in the state is struggling with higher levels of food insecurity than before the onset of COVID-19. One in five of those struggling here in Central Florida are children.

Yet a question that THRIVE has pondered is whether food insecurity is an economic stability issue or a health issue. The best answer seems to be, like so many of the interrelated THRIVE pillars, both. Defining food insecurity is helpful here.

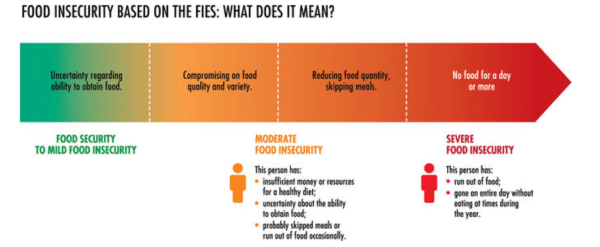

According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, food insecurity is defined as lacking “regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life.” Both the UN and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) delineate levels of food insecurity. Given Thrive’s reliance on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, the UN’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) is an apt reference point for Central Florida (see figure below).

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/hunger/en/

Two leading causes of food insecurity are an inability to afford adequate, nutritious food and lack of access to such food (i.e. living in a “food desert,” where there is a shortage of grocery stores and an overabundance of unhealthy food options nearby).

With this understanding in mind, it becomes clear that while the leading causes of food insecurity—unaffordability and lack of access—may be seen as economic issues, the long-term results of food insecurity—malnutrition and mental illness—are clearly health issues. Research abounds on the individual and public health ramifications of unchecked food insecurity among children and adults, including obesity, diabetes, increased hospitalizations, anxiety, and depression. Yet over time, these health outcomes impact the larger economy, again showing the interrelatedness of the two THRIVE pillars.

So how does Central Florida fare on food insecurity? More than half a million Floridians are struggling with food insecurity in the six counties included in Feeding America’s Central Florida estimates (Brevard, Lake, Orange, Osceola, Seminole, Volusia). Orange County has the third-highest rate of food insecurity in the area, at over 14 percent of county residents.

The COVID-19 pandemic is only partially to blame, as food insecurity was a Central Florida concern long before 2020. Moreover, many emergency solutions meant to help those facing food insecurity as a result of the pandemic are hastily being rolled back or disregarded entirely.

Food distribution programs for children, families, and older adults continue to make an impact on food insecurity in our community. Recent research shows Central Florida food distribution and security programs offer a $13 return on every $1 investment and redirection of over 22,000 tons of food that would have been wasted each year. These efforts work, but they have yet to fully address the growing need.

As a result, some advocates are pushing to expand the definition of a food desert (e.g., food apartheid, food oppression) to better describe the systemic policies and planning decisions that relegate low-income and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities to these areas more than other Americans. For decades, poor decision making created food deserts, stagnated Central Floridians’ income-earning potential, and limited the scope of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The residual approach of providing food to those in need is only one piece of the solution. Investing in the long-term economic stability and health of all Central Floridians must be too.

“The only true and sustainable prosperity is shared prosperity.” –Joseph E. Stiglitz, Nobel laureate economist and professor